Canada’s Military Spending Surge: A Costly Illusion

NATO already vastly outspends other countries.

Since the beginning of the Ukraine-Russia war in 2022, mainstream political discourse in Canada has largely shifted towards accepting that we should increase military spending to 2% of GDP—an arbitrary target set by NATO. This goal was affirmed by Justin Trudeau’s government, which aimed to reach the 2% target by 2032. Now, Prime Minister Mark Carney is promoting an even more aggressive timeline, seeking to hit the target two years earlier, by 2030.

Surprisingly, some prominent progressive politicians in Canada also support increasing military spending. Manitoba’s NDP Premier Wab Kinew stated in July 2024 that “if we don’t hit that two per cent target within the next four years … it’s going to become a trade issue,” while British Columbia’s NDP Premier David Eby has urged the federal government to spend more on the military. Even the federal NDP under Jagmeet Singh agreed not to criticize military budget increases as part of its 2022 supply and confidence agreement with the Trudeau Liberals. (Curiously, while Conservatives under Pierre Poilievre predictably support growing the military, Poilievre has so far resisted promising to meet the 2% target should he lead the next government.)

What will it cost?

The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) provided a comprehensive estimate in October 2024, concluding that Canada would need to nearly double military spending from 2024-25 levels to reach 2% of GDP by 2032. In dollar terms, this means an additional $40 billion per year within seven years.

To put this in perspective, that’s more than the federal government’s annual cost for the national child care plan. It also exceeds the projected costs of a universal national pharmacare plan or the dental care plan currently being rolled out. And it far surpasses the federal share of a hypothetical universal free-tuition program for post-secondary education, as the Green Party of Canada proposed in its 2019 and 2021 federal election platforms.

By any reasonable comparison, boosting military spending to this degree represents a profound opportunity cost. For years to come, it will likely prevent the expansion of social programs that make Canada a more equitable society—or even lead to their reduction.

Is Canada a low spender in NATO?

Canada currently spends about 1.37% of GDP, or $41 billion, on the military. Advocates for increased military budgets argue that Canada is a laggard because, measured as a percentage of GDP, only four NATO countries—Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Spain—spend less than us.

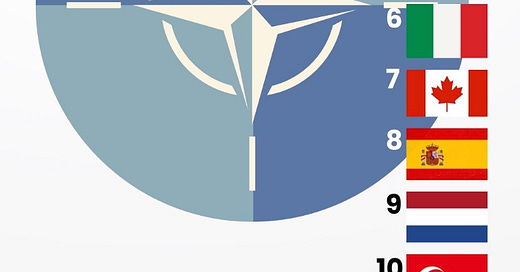

Yet there’s another way to look at it. Measured in actual dollars, Canada ranks seventh out of NATO’s 32 member states, trailing only the U.S., Germany, the U.K., France, Poland, and Italy. In other words, Canada spends more on its military than 24 other NATO members. (Iceland, a founding NATO member, does not have a standing military.)

With the substantial public funds our government devotes to the military, Canada has made significant contributions to numerous overseas military missions since the beginning of the millennium. For better or worse, Canada was among the first countries to join the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan following the attacks of September 11. A few years later, Canada took on a lengthy leadership role in the volatile Kandahar province of Afghanistan as part of NATO’s ISAF “nation-building” mission. This intervention is conservatively estimated to have cost $18 billion and led to the deaths of 158 soldiers and one diplomat.

Even before withdrawing from Afghanistan, Canada deployed CF-18s to drop nearly 700 bombs on Libya in 2011 as part of a NATO mission. Then in 2014, Canada sent CF-18s to bomb targets in Iraq and Syria, this time as part of a new U.S.-led coalition of the willing. That same year, Canada deployed fighter jets to Europe following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. And in 2017, Canada began leading a multinational battle group under NATO in Latvia. By 2026, plans call for the expanded deployment of up to 2,200 Canadian military personnel as part of this mission.

Christian Leuprecht and Joel Sokolsky, political scientists at the Royal Military College, argue that Canada’s military “capacity … is popular, robust, competent, and well-equipped.” They add: “Canada is one of only five NATO member countries that maintains a full-spectrum military … Canada’s mantra has always been not to get hung up on expenditure, and to focus on capability and commitment instead, since Canada consistently outperforms on both.”

Whatever one thinks of the various missions mentioned above, and there are plenty of reasons for concern, Canada has a lengthy record of contributing to international military operations.

NATO already outspends everyone else

The near-universal support for increasing NATO budgets ignores the glaring reality that NATO already vastly outspends other countries. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), in 2023 NATO members collectively spent USD $1.34 trillion—yes, trillion—on their militaries, accounting for 55% of global expenditures. In contrast, Russia spent $109 billion, and China spent $296 billion. In other words, NATO’s total military budget is ten times that of Russia’s and three times that of Russia and China combined. Even if we exclude the U.S., all other NATO countries still spend more—$425 billion—than Russia and China combined.

On a per capita basis, the disparity is also striking. NATO’s collective population of 960 million means it spends $1,395 per person on the military. By contrast, Russia, with a population of 146 million, spends $746 per person, and China, with a population of 1.41 billion, spends only $210 per person.

Following the logic of those who claim bigger military budgets will make us safer, this enormous gap in spending should have deterred Russia. Yet, it did not. Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 and has since been effectively engaged in an expensive proxy war with NATO. Collectively, NATO and its allies have provided Ukraine with $137 billion in military support so far. Yet, Russia is in no rush to end the war.

If outspending Russia 10-to-1 didn’t prevent war, how can anyone credibly argue that increasing NATO’s spending advantage even higher will make us safer? Why should Canada contribute to such a military buildup?

The burden of proof lies with those advocating for increased military spending, but so far, the evidence is overwhelmingly against bigger budgets. In upcoming posts, we’ll take a deeper, critical look at the assumptions underlying the push for increased military spending—namely, the perceived threats from Russia and China and the pressure from the U.S. We’ll also look at the societal opportunity costs of embarking on this ambitious spending spree in the coming years.